For many visitors to Japan today, kites (tako) and carp streamers (koinobori) are seen as distinct traditions: kites are flown for fun or at festivals, while colorful koinobori decorate the skies during Children’s Day in May, symbolizing hopes for children’s health and strength.

But in Edo-period Japan (1603–1868), the line between these two seemingly separate customs was once far blurrier. In fact, there was a time when people even used carp streamer terminology as a clever loophole to bypass government kite bans.

Let’s dive into this surprising historical overlap—and what it reveals about life and government control during the Edo era.

Kite Flying in Edo: From Hobby to Social Problem

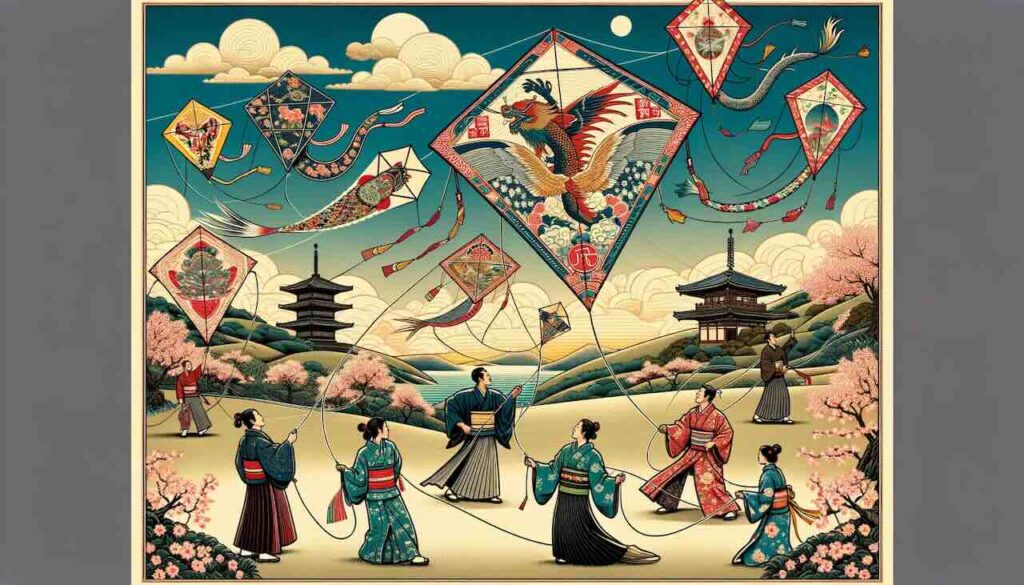

During the Edo period, kite flying flourished as a form of popular entertainment among commoners. Particularly in urban Edo (modern-day Tokyo), colorful handmade kites filled the skies, especially during the New Year season.

However, as the popularity of kites grew, they became entangled in larger social issues, which eventually triggered government intervention.

1. Gambling and Kite Competitions

- Competitive kite flying often involved gambling: people placed bets on whose kite would fly higher, last longer, or cut down rival kites in aerial battles.

- These gambling activities led to disputes, debt, and disorder among the lower classes.

- The Tokugawa shogunate, which prioritized social stability and rigid hierarchy, viewed gambling as a dangerous destabilizing force.

2. Fire Hazards

- Edo was a densely packed city of wooden houses and narrow streets, making it extremely vulnerable to fires.

- A snapped kite string or runaway kite could easily land on rooftops, tangle in thatched roofs, and spark fires.

- The government, constantly wary of urban fires, cited these risks as further justification for regulating kite flying.

The Kite Flying Ban: Shogunate Control Over Daily Life

To curb these growing problems, the Tokugawa government issued bans on kite flying:

- These bans weren’t necessarily permanent but were often seasonal or situational, particularly during times of heightened fire risk.

- The prohibition reflected the shogunate’s broader policy of strict moral and social control over commoners, a hallmark of Edo-period governance.

While kite flying may seem harmless today, in Edo society it became a symbol of the state’s willingness to interfere even in seemingly trivial aspects of daily life.

The “Ikanobori” Loophole: Evading the Ban with Wordplay

In response to these bans, some clever citizens tried to circumvent regulations by rebranding their kites under a different name: ikanobori (鯉幟 or 鯉上り).

- “Ikanobori” (more commonly pronounced koinobori today) refers to carp-shaped streamers traditionally flown to celebrate children’s strength and success.

- During the Edo period, some kite flyers labeled their kites as ikanobori—implying that they were festive carp decorations rather than prohibited flying objects.

- The strategy played on the ambiguity of terms and the cultural tolerance for certain festival symbols.

However, this ruse didn’t go unnoticed. Historical records suggest that shogunate officials eventually cracked down on this loophole, extending restrictions to any kite-like object flown in defiance of the bans.

Kites, Carp Streamers, and Modern Japan: Now Clearly Separated

In contemporary Japan, kites and carp streamers have diverged into two clearly distinct traditions:

- Kites (tako, 凧) are flown recreationally or during seasonal festivals, with strong regional variations in design and style.

- Koinobori (鯉のぼり) are specifically associated with Children’s Day (May 5th), flown to celebrate children’s healthy growth and prosperity.

Today, the word “ikanobori” has faded from common use, and no one mistakes carp streamers for kites anymore. Moreover, modern kite flying practices emphasize safety protocols that would have been unimaginable in Edo:

- Avoiding power lines and urban rooftops.

- Using durable, break-resistant kite strings.

- Designated flying areas with open spaces.

What the Kite Ban Tells Us About Edo Society

The Edo-period kite bans are more than just a quirky historical anecdote — they offer insight into how the shogunate managed urban life:

- The bans reflected deep concern about public order, fire prevention, and class stability.

- They demonstrate how the Tokugawa regime actively regulated even leisure activities that might threaten peace or encourage vice.

- Citizens’ creative evasion tactics, like calling kites “ikanobori,” reflect commoners’ quiet resistance within the rigid control system.

Summary

Yes, Edo-period Japan truly did ban kite flying—and yes, some citizens cheekily tried to get around it by calling their kites “ikanobori.” This obscure historical episode offers a glimpse into Japan’s complex balancing act between public safety, social control, and popular culture.

Today, both kites and carp streamers have become cherished cultural symbols, each with their own seasonal role — free from government bans, but with a nod to their shared history.

The next time you see colorful kites soaring or koinobori fluttering in Japan’s spring breeze, you’ll know that their past is more intertwined than meets the eye.