Among the many unique figures in Japan’s long history, few are as fascinating — or as paradoxical — as the sohei, or warrior monks. These were Buddhist monks who combined religious devotion with military skill, playing a powerful role in shaping Japan’s medieval political and religious landscape. Their existence challenges modern assumptions about the relationship between spirituality and violence, making them one of the most intriguing phenomena in Japanese history.

The Rise of Sohei: Origins in the Heian and Kamakura Periods

The emergence of sohei can be traced back to the late Heian period (794–1185) and the early Kamakura period (1185–1333), a time when Buddhist temples in Japan grew increasingly wealthy, powerful, and deeply entwined in political affairs. Major temples such as Enryaku-ji on Mount Hiei and Kofuku-ji in Nara amassed vast landholdings, political influence, and substantial wealth, making them targets for both rival temples and secular authorities.

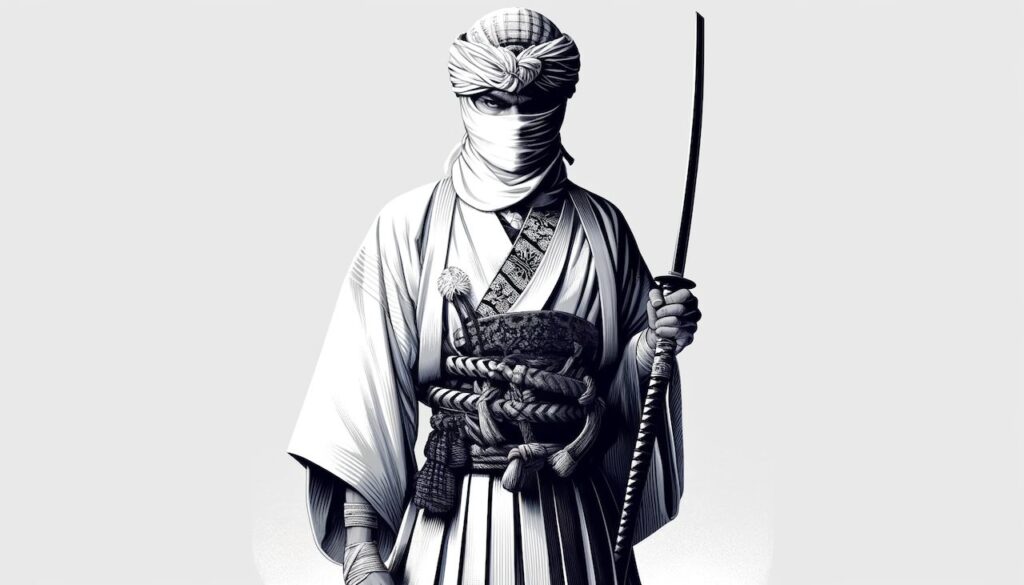

To defend their property, rights, and religious interests, these temples organized their own private armies composed of armed monks — the sohei. Many of these warrior monks came from samurai backgrounds or were trained in martial arts after joining monastic life, blending two very different worlds: the sword and the sutra.

Roles and Organization of the Warrior Monks

At their core, sohei were tasked with protecting their temples, lands, and religious communities. However, their influence extended far beyond simple defense:

- They often acted as military forces in disputes between rival temples or factions.

- They intervened in political conflicts, sometimes even threatening imperial or shogunate authority.

- They wielded both martial and ceremonial authority, participating in religious rituals while remaining prepared for battle.

Temples such as Enryaku-ji became military fortresses, housing thousands of sohei. Famous conflicts, like the battles between Enryaku-ji and Miidera or confrontations with the Taira and Minamoto clans, demonstrate the degree to which sohei shaped the power struggles of medieval Japan.

Their weapons included swords, bows, spears, and later, firearms. The naginata — a long polearm — became particularly associated with sohei for its effectiveness both in battle and as a symbol of their unique status.

The Paradox of Violence in Buddhist Practice

The existence of warrior monks presents a striking contradiction to Buddhist precepts, which generally forbid killing and promote compassion for all living beings. However, Japanese Buddhism during this period developed highly syncretic forms, blending Shinto beliefs, local customs, and practical adaptations to the turbulent times.

In this context, defending the temple and its sacred space was interpreted as protecting the Buddhist law (dharma). While bloodshed was regrettable, the survival of the faith was seen as paramount. This flexible approach to religious precepts allowed sohei to justify their military actions as a necessary means of preserving Buddhism’s presence and influence in Japan.

However, this justification was not without controversy, even among Buddhists themselves. The militarization of temples was often seen as evidence of corruption and spiritual decline, contributing to later calls for reform.

Decline and Suppression: The End of the Warrior Monks

As Japan entered the Sengoku period (15th–16th centuries) — an era of nearly constant warfare — sohei became deeply entangled in conflicts across the country. Some allied themselves with powerful warlords; others fought to defend their own autonomy.

Eventually, their political and military power attracted the attention of ambitious unifiers such as Oda Nobunaga, who viewed the sohei as threats to national stability. In 1571, Nobunaga famously destroyed Enryaku-ji on Mount Hiei in a brutal campaign, massacring its sohei and burning much of the temple complex. This marked the beginning of the end for the warrior monks as a significant political force.

By the start of the Edo period (1603–1868), Japan’s long-lasting peace under Tokugawa rule eliminated the conditions that had allowed sohei to exist, and their era came to a close.

The Legacy of Sohei in Japanese History and Culture

Though the sohei no longer exist, their legacy continues to fascinate historians and cultural scholars for several reasons:

- They embody the tension between spiritual ideals and worldly power.

- They offer a unique lens to explore how religious institutions adapt to political realities.

- They reflect the distinctive syncretism of Japanese Buddhism, blending religion, politics, and martial tradition.

The story of the sohei also echoes broader questions still debated today:

How do spiritual communities navigate violence and self-defense? Can religious institutions wield political power without compromising their values? The history of Japan’s warrior monks remains relevant far beyond its own cultural boundaries.

Conclusion: The Paradoxical Warriors of Faith

The sohei of medieval Japan challenge simple narratives of religion and nonviolence. They stood as both protectors of sacred temples and participants in political warfare, operating at the crossroads of faith, survival, and power.

Their story offers a complex, thought-provoking window into Japan’s medieval past — one that continues to invite reflection on the sometimes uneasy relationship between belief, duty, and force.