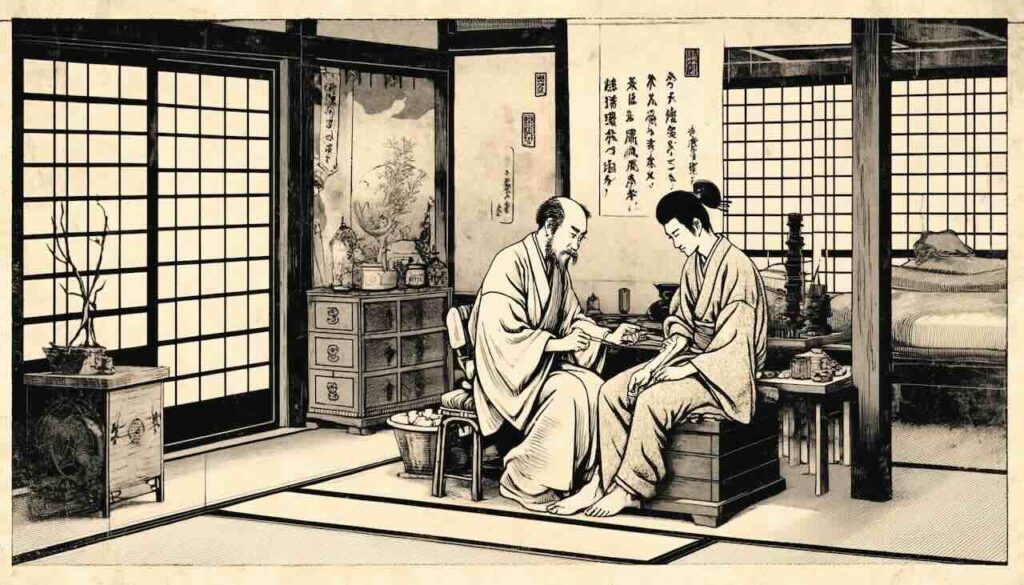

In the quiet elegance of a traditional Japanese home or temple, beauty often reveals itself in subtle details. Look above the sliding doors and you may notice a finely carved or delicately painted panel that seems to float between rooms. This is the ranma (欄間)—a uniquely Japanese architectural feature that blends function, artistry, and spiritual sensitivity into a single graceful element.

What Is a Ranma?

A ranma is a decorative transom panel installed above doorways, sliding doors (fusuma), or shoji screens in traditional Japanese architecture. While their initial function was practical—facilitating air circulation and natural light between rooms—ranma have long transcended mere utility to become exquisite works of art in their own right.

Ranma are typically crafted from wood, paper, or silk, and often feature intricate carvings or paintings. Common motifs reflect the Japanese reverence for nature and seasonal cycles: cranes, pine trees, waves, dragons, bamboo, plum blossoms, and other elements rich in symbolism.

The Functional Beauty of Ranma

1. Natural Light and Ventilation

In Japan’s hot, humid summers, ranma allowed air to circulate between rooms without compromising privacy. The openwork designs also let in filtered light, creating gentle transitions between spaces.

2. Visual Separation and Spatial Harmony

While not fully closing off spaces, ranma provide a sense of boundary while maintaining openness—perfectly embodying the Japanese principle of ma (間), or “space between.” They create a seamless flow that allows each room to breathe while remaining part of a harmonious whole.

3. Artistic and Spiritual Expression

Beyond function, ranma serve as visual focal points, showcasing regional craftsmanship, symbolism, and seasonal awareness. Many designs carry auspicious meanings meant to bring longevity, good fortune, or spiritual protection to the home.

The Origins and Evolution of Ranma

Chinese Influence and Early Adoption

The concept of decorative transoms likely arrived from China during the Asuka period (6th–8th centuries) alongside the introduction of Buddhism and temple architecture. Early examples were mostly found in imperial palaces and religious structures.

Heian Period Refinement

By the Heian period (794–1185), ranma began appearing in aristocratic residences, evolving into sophisticated design elements tailored to Japanese aesthetics. Delicately painted or carved panels reflected the refined court culture of the era.

Widespread Use in the Edo Period

During the Edo period (1603–1868), ranma became common in the residences of samurai, merchants, and wealthy townspeople. Skilled artisans developed regionally distinct styles in cultural centers such as Kyoto, Kanazawa, and Edo (Tokyo). Ranma transformed into a widely appreciated craft, no longer limited to nobility or temples.

Types of Ranma: A Showcase of Japanese Artistry

Carved Ranma (Kibori Ranma)

Elaborate wooden panels intricately carved with natural, mythological, or literary scenes. Often found in temples, shrines, and prestigious homes, these showcase exceptional woodcarving skills passed down through generations of artisans.

Openwork Ranma (Sukashi Ranma)

Featuring pierced or lattice-like patterns, these designs allow greater airflow and light penetration. Their airy, geometric beauty often complements merchant townhouses (machiya) and tea houses.

Kumiko Ranma

Created using the meticulous kumiko technique, thin wooden slats are assembled without nails or glue into precise geometric patterns. The resulting transoms express understated elegance and mathematical precision.

Painted Ranma

Delicate paintings on silk or paper are mounted within wooden frames, turning the transom into a horizontal scroll. Popular subjects include birds, flowers, landscapes, and seasonal motifs, rendered with a soft, ethereal quality.

Ranma in Contemporary Architecture

Though modern homes no longer require ranma for ventilation, architects and designers continue to draw inspiration from these timeless elements:

- Restored machiya (traditional townhouses) often feature preserved or newly crafted ranma.

- High-end ryokan (traditional inns) and cultural centers incorporate ranma to evoke a sense of refined authenticity.

- Modern architects experiment with glass, metal, or acrylic ranma, blending tradition with minimalism.

- Some contemporary homes use ranma purely as art installations or symbolic design statements, connecting modern life to Japan’s architectural heritage.

The Deeper Meaning Behind Ranma

Ranma reflects several core principles of Japanese aesthetics:

- Integration of nature and structure: Nature is not excluded but framed and referenced inside living spaces.

- Simplicity with depth (wabi-sabi): Beauty emerges not from ostentation but from subtlety, impermanence, and craftsmanship.

- Respect for craft (shokunin spirit): Each ranma is a labor of love, often hand-carved or painted by skilled artisans.

Summary

More than simple decorations, ranma embody Japan’s architectural philosophy of functional beauty. They serve as a bridge between rooms, between tradition and innovation, and between practicality and poetry. Whether carved from fine cedar, assembled from delicate kumiko lattices, or painted with seasonal scenes, each ranma offers a quiet meditation on nature, space, and craftsmanship.

For visitors to Japan, noticing these elegant transoms offers not just aesthetic pleasure but a deeper glimpse into the heart of Japanese design tradition—where every small detail carries meaning, history, and artistry.