When discussing Japan’s history, few topics capture foreign curiosity as much as Sakoku (鎖国) — Japan’s self-imposed isolation during the Edo period. But far from being simple national seclusion, Sakoku was a complex strategy that allowed Japan to maintain political stability, preserve cultural identity, and carefully control limited foreign interaction for over two centuries.

What Was Sakoku?

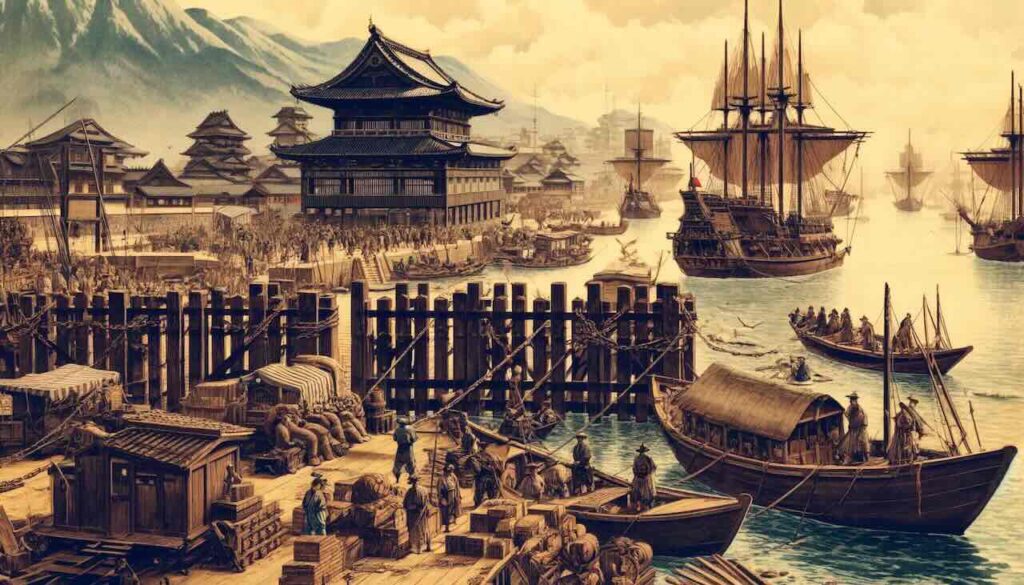

The term Sakoku — literally meaning “closed country” — refers to the foreign relations policy implemented by the Tokugawa shogunate during the Edo period (1603–1868). While often described as absolute isolation, Sakoku was actually a carefully managed system of controlled and selective international engagement.

Key features of Sakoku included:

- Severe restrictions on foreign entry and Japanese emigration — Japanese citizens were forbidden to leave, and returnees were often executed as a deterrent.

- Limited trade partnerships — Foreign trade was restricted to a few carefully monitored partners: primarily the Dutch, Chinese, Koreans, and the Ryukyu Kingdom.

- The port of Nagasaki (Dejima) served as the main gateway for international trade.

- Strict prohibition of Christianity, seen as a destabilizing foreign influence.

Sakoku was formalized by the 1639 Edicts, following earlier restrictions implemented after rising concerns over European colonial ambitions and Christian missionary activities.

Why Did Japan Adopt Sakoku?

The decision to enter isolation was not made out of fear alone, but rather from a combination of political, religious, and strategic calculations:

- Control over foreign religions: The Tokugawa shogunate viewed Christianity, brought by European missionaries, as a potential threat to its authority and Japan’s social order.

- Defense against colonial powers: The aggressive expansion of European empires in Southeast Asia raised fears of similar interventions in Japan.

- Internal stability: The Tokugawa regime sought to minimize external influences that could disrupt its rigid social hierarchy (the feudal class system).

- Preservation of cultural identity: Isolation allowed Japan to protect its unique arts, traditions, and governing systems from Western intrusion.

In this sense, Sakoku was less about pure isolation and more about asserting domestic sovereignty and maintaining peace in an era of global imperialism.

Other Historical Isolationist Policies Around the World

Japan’s Sakoku was not entirely unique in world history. Several other nations employed forms of controlled isolation during different periods:

| Country | Isolationist Policy | Period |

|---|---|---|

| China (Ming Dynasty) | Maritime trade bans (Haijin policy) | 16th century |

| Korea (Joseon Dynasty) | Limited contact with China and Japan | 17th–19th centuries |

| Bhutan & Tibet | Closed off from outside influences | Pre-20th century |

However, Japan’s Sakoku stands out for its longevity, strict enforcement, and its success in maintaining relative peace (the Pax Tokugawa) for over two centuries.

Advantages of Sakoku

Despite its eventual end, Sakoku offered several benefits to Tokugawa Japan:

- Cultural preservation: Japanese arts, literature, and traditional crafts flourished in a relatively stable, self-contained environment.

- Political stability: With fewer foreign entanglements, Japan avoided the wars and conflicts that engulfed many contemporary nations.

- Control over foreign influence: Christianity was suppressed, preventing religious conflicts that destabilized other societies.

- Limited external threats: Japan escaped the direct colonial exploitation experienced by many neighboring countries.

The Edo period’s prosperity, urban growth (such as the rise of Edo, now Tokyo), and rich cultural output were partially enabled by the peace maintained under Sakoku.

Disadvantages of Sakoku

However, isolation also came at a cost:

- Technological stagnation: Japan fell behind during the Industrial Revolution, delaying modernization.

- Limited scientific and medical knowledge: Most Western advancements were only available through restricted Dutch sources (Rangaku or “Dutch learning”).

- Vulnerability to external pressure: When Western powers arrived in the 19th century, Japan was unprepared to negotiate from a position of strength.

- Unequal treaties: The forced opening by Commodore Perry in 1853 led to a series of unequal treaties that deeply affected Japan’s national psyche.

Ultimately, these challenges contributed to the collapse of the Tokugawa shogunate and the beginning of the Meiji Restoration in 1868.

Sakoku’s End and Japan’s Rapid Transformation

In 1853, Commodore Matthew Perry’s “Black Ships” (Kurofune) arrived in Tokyo Bay, demanding the opening of Japanese ports. This led to:

- The Treaty of Kanagawa (1854), officially ending Sakoku.

- A wave of foreign influence, trade, and technological exchange.

- Japan’s rapid modernization during the Meiji era, propelling it from isolation to industrial power within a few decades.

Ironically, Japan’s strong cultural foundation, carefully preserved during Sakoku, helped it adapt quickly once forced to modernize.

Summary

Japan’s Sakoku policy was not simply an act of isolation, but a carefully crafted strategy for maintaining domestic control, cultural purity, and national sovereignty during a time of expanding global empires. While it protected Japan’s internal stability for over two centuries, it also delayed Japan’s entry into the global industrial revolution, leaving the country vulnerable when forced open by foreign powers.

Today, Sakoku remains a uniquely Japanese response to globalization pressures of the early modern world — a policy that continues to fascinate historians, political scientists, and cultural observers alike.