Few aspects of daily life in Japan reflect the country’s blend of tradition, community, and design quite like its public bathhouses, known as sento (銭湯). More than simple places to wash, bathhouses have long served as vital hubs for relaxation, social interaction, and cultural identity.

Let’s explore the rich history, unique customs, and ongoing evolution of Japanese bathhouse culture — including the little-known history of mixed bathing that once defined the experience.

The Origins of Japanese Bathhouses

Buddhist Roots: The Birth of Bathing Culture

Japan’s public bathing tradition traces its roots to the Nara period (710–794 CE), coinciding with the spread of Buddhism. Buddhist temples often featured yokudō (浴堂), bathing halls where monks purified themselves as part of their spiritual practice.

Gradually, this religious cleansing practice extended to the general population. By the Heian period (794–1185 CE), more accessible public bathhouses called yuya (湯屋) emerged, offering simple communal bathing spaces.

Edo Period: The Rise of Urban Bathhouses

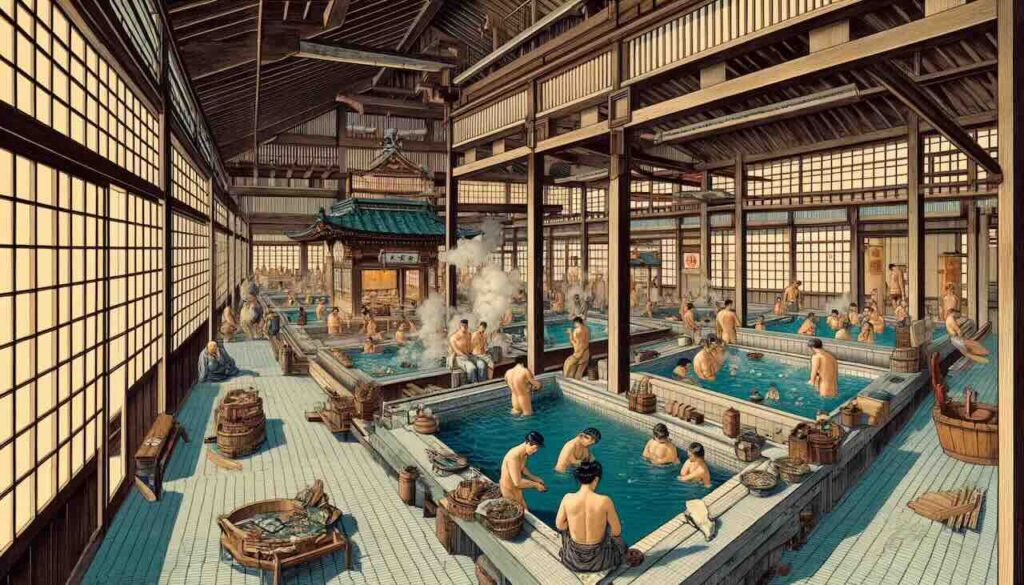

Japan’s bathhouse culture flourished during the Edo period (1603–1868), particularly in the rapidly growing city of Edo (modern Tokyo):

- Hundreds of small neighborhood bathhouses, called nagaya-buro (row house baths), served the daily needs of ordinary townspeople.

- Bathhouses offered not only cleanliness but also a place for socializing, exchanging gossip, and building community ties.

- At this stage, mixed bathing (konyoku, 混浴) was entirely normal and unremarkable, reflecting the more relaxed attitudes toward nudity in pre-modern Japan.

Architecture and Design: The Charm of Sento

Traditional Sento Features

- Wooden structures with prominent tiled roofs, often inspired by Shinto shrine or temple architecture.

- Distinct entrances for men and women (a practice introduced later).

- Noren (fabric curtains) hung at the entrance, symbolizing both welcome and privacy.

- A large, shared bathing pool (ofuro, お風呂) where bathers soaked together.

Modern Innovations

While some classic sento remain, many modern facilities now feature:

- Super sento: large-scale bathing complexes with multiple pools, saunas, massage services, and dining areas.

- Themed baths using mineral waters, aromatic herbs, or even wine and sake.

- Enhanced design elements that blend traditional aesthetics with contemporary comfort.

The Transition from Mixed Bathing to Gender Separation

The Age of Mixed Bathing

- In Edo-period Japan, mixed bathing was routine, driven by practical reasons:

- Limited space in urban bathhouses.

- Cultural norms that did not strongly associate nudity with sexuality.

- Bathing viewed as a functional, not private, activity.

Western Influence and Changing Norms

- With the arrival of Western cultural influences during the Meiji period (1868–1912), attitudes toward public nudity began to shift.

- Government policies promoted gender-separated bathing, citing both hygiene and moral reform.

- Over time, most public bathhouses introduced separate male and female bathing areas — a practice still followed in modern Japan.

The Persistence of Mixed Bathing

- While largely eliminated in urban sento, mixed bathing still survives in some rural hot springs (onsen) and traditional inns, offering visitors a glimpse into Japan’s earlier bathing customs.

- Certain remote konyoku onsen continue to attract curious tourists seeking an authentic historical experience.

The Role of Bathhouses in Community Life

Bathhouses have always functioned as more than just places to bathe:

- A daily gathering place for neighbors to catch up on news.

- A refuge for those without private baths at home.

- A center for intergenerational bonding, with children, parents, and grandparents sharing space.

Even today, many small neighborhood bathhouses retain this intimate, communal atmosphere, offering a rare escape from modern isolation.

The Rise of Sauna and Bath Towel Culture

Saunas in Japan

- In recent decades, saunas have become a popular addition to both sento and onsen facilities.

- The Japanese sauna experience often includes:

- Alternating between hot steam rooms and cold baths.

- The practice of totonou (整う) — reaching a state of deep physical relaxation after repeated hot-cold cycles.

Bath Towel Customs

- Most bathhouses rent or sell small towels (tenugui) at the entrance.

- The small towel is often used to:

- Wash the body before entering the bath.

- Cover modesty while walking between changing rooms and baths.

- Never placed inside the bath itself, to preserve cleanliness.

This towel etiquette reflects Japan’s careful blending of personal modesty and communal bathing harmony.

The Modern Revival of Sento Culture

Rediscovery by Younger Generations

- In recent years, many younger Japanese have rediscovered sento as:

- Affordable wellness experiences.

- Instagrammable cultural sites.

- A nostalgic link to family traditions.

The Super Sento Phenomenon

- Super sento offer a hybrid spa experience, blending traditional bathing with:

- Massage services

- Beauty treatments

- Relaxation lounges

- Family-friendly attractions

Bathhouses as Cultural Heritage

- Some historical sento are now recognized as important cultural properties, receiving preservation efforts to maintain their architecture and community role.

Conclusion: Why Japanese Bathhouse Culture Endures

Japan’s bathhouse culture has survived for over 1,300 years because it reflects the Japanese approach to harmony, community, and mindfulness:

- A space for both physical and social cleansing.

- A communal ritual that bridges generations.

- A uniquely Japanese intersection of tradition and innovation.

Whether you’re soaking in a quiet neighborhood sento or relaxing in a sprawling super sento, you’re participating in a living tradition that continues to adapt while preserving its timeless essence.

If you ever visit Japan, don’t miss the opportunity to step into a sento or onsen. It’s one of the most deeply authentic—and uniquely Japanese—cultural experiences you can have.