When we think of early modern Japan, we often picture samurai, tea ceremonies, and meticulously ordered society. Yet behind the elegant facade of Edo-period life, Japan’s medical system was quietly undergoing its own fascinating transformation. Over the course of the Edo period (1603–1868), Japanese medicine evolved from a largely unregulated craft into a more professionalized and scientifically informed discipline, blending traditional Eastern practices with emerging Western knowledge.

- Medicine in Early Edo Japan: Open Access and Apprenticeship

- The Rise of Medical Knowledge: Chinese, Japanese, and Western Traditions

- The Arrival of Rangaku: Western Medicine Enters Japan

- The Government Steps In: Regulation and Professionalization

- Public Health Systems in the Edo Period

- Medicine at the Edge of Modernization

- Summary

Medicine in Early Edo Japan: Open Access and Apprenticeship

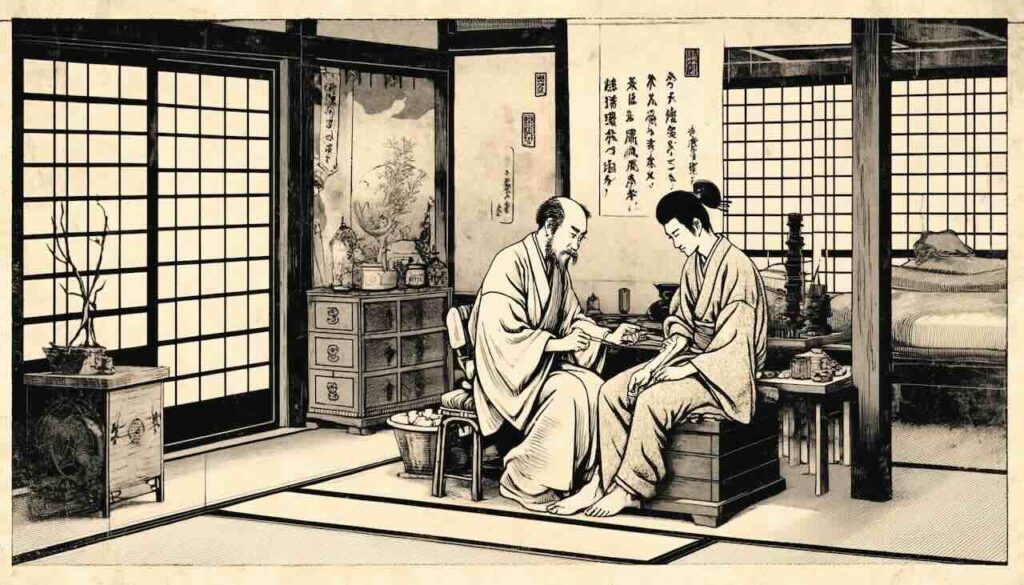

In the early years of the Edo period, medical practice in Japan was surprisingly open. Nearly anyone could claim the title of doctor (isha) with little or no formal certification. Most physicians learned their craft through apprenticeship (deshi system), studying under established practitioners who passed down medical techniques orally or through private manuscripts.

While some doctors were highly skilled and well-respected, others lacked even basic competence. This absence of standardized training or government oversight led to a wide variance in the quality of care. As a result, so-called “quack doctors” (ニセ医者) often operated freely, offering dubious remedies to unsuspecting patients.

The Rise of Medical Knowledge: Chinese, Japanese, and Western Traditions

Despite the lack of formal regulation, Japan already had a rich foundation of medical knowledge rooted in:

- Traditional Chinese medicine (Kampo), which heavily influenced Japanese practice through texts like the Huangdi Neijing.

- Indigenous Japanese herbal and folk remedies.

- Buddhist and Shinto healing rituals.

As the Edo period progressed, Japanese physicians began refining and systematizing Kampo practices, developing distinct Japanese interpretations of Chinese theory.

The Arrival of Rangaku: Western Medicine Enters Japan

A major turning point came in the 18th century with the introduction of Rangaku (蘭学, “Dutch learning”) — a window to European scientific knowledge through limited contact with Dutch traders at Nagasaki’s Dejima trading post.

Key contributions of Rangaku to Japanese medicine included:

- Anatomy: Dissections revealed structural details previously unknown in Eastern medicine.

- Surgery: New surgical techniques were introduced.

- Diagnostics: Western tools like stethoscopes and thermometers gradually entered practice.

- Publications: The landmark translation of Dutch anatomy books (Kaitai Shinsho, 1774) marked Japan’s first comprehensive engagement with modern medical science.

Rangaku represented Japan’s early encounter with scientific empiricism, paving the way for more evidence-based practice while coexisting with Kampo traditions.

The Government Steps In: Regulation and Professionalization

As knowledge advanced, so too did concerns over public safety. The Edo government (the Tokugawa shogunate) and regional domains (han) began introducing measures to control the proliferation of unqualified doctors:

Licensing and Certification

- Several domains implemented medical licensing exams to verify minimum levels of skill and knowledge.

- The central shogunate encouraged qualified doctors to register, formalizing their professional status.

Supervision and Oversight

- Local officials were empowered to investigate complaints of malpractice.

- Certain cities appointed official physicians (御用医者, goyō isha) who were trusted by the government to oversee medical standards.

Medical Education and Schools

- The first private medical academies (igakujuku) emerged, offering more systematic instruction.

- Some domains sponsored official medical schools for their retainers.

- Prominent schools blended both Kampo and Rangaku, creating a hybridized curriculum that reflected Japan’s intellectual pragmatism.

Publication of Medical Texts

- Medical knowledge was increasingly codified through printed manuals and guidebooks, improving accessibility to standardized treatments.

- These texts allowed knowledge to spread far beyond elite circles.

Public Health Systems in the Edo Period

Surprisingly, public health in Edo Japan was relatively advanced for its time:

- Urban centers like Edo and Osaka had organized medical districts and designated doctors for different neighborhoods.

- Charity clinics (jyushinjo) provided free medical care for the poor, sponsored by wealthy merchants or temples.

- Communal baths, attention to cleanliness, and sophisticated sewer systems helped control infectious diseases.

Though not comparable to modern healthcare, Edo-period Japan demonstrated remarkable local-level management of health services within a feudal context.

Medicine at the Edge of Modernization

By the late Edo period, Japan had developed a complex hybrid medical system blending:

- Kampo (traditional medicine)

- Rangaku (Western medicine)

- Government regulation and formalized training

When the Meiji Restoration (1868) finally opened Japan to full-scale Westernization, the foundation laid during the Edo period allowed Japan to rapidly modernize its healthcare system and adopt global medical standards without entirely discarding its traditions.

Summary

The evolution of medicine during the Edo period reflects Japan’s broader genius for adaptation and synthesis. From an open, apprenticeship-based system vulnerable to quackery, Japan gradually established professional standards, embraced Western science through Rangaku, and created a regulated medical infrastructure. This transformation not only protected patients but also prepared Japan to make one of the most successful transitions into modern medicine seen anywhere in Asia.

For modern visitors curious about Japan’s history, the story of Edo-period medicine offers a compelling glimpse into how even fields as technical as healthcare were shaped by Japan’s unique blend of pragmatism, craftsmanship, and openness to selective foreign influence.